ATAC-Qwen-VL

Introduction

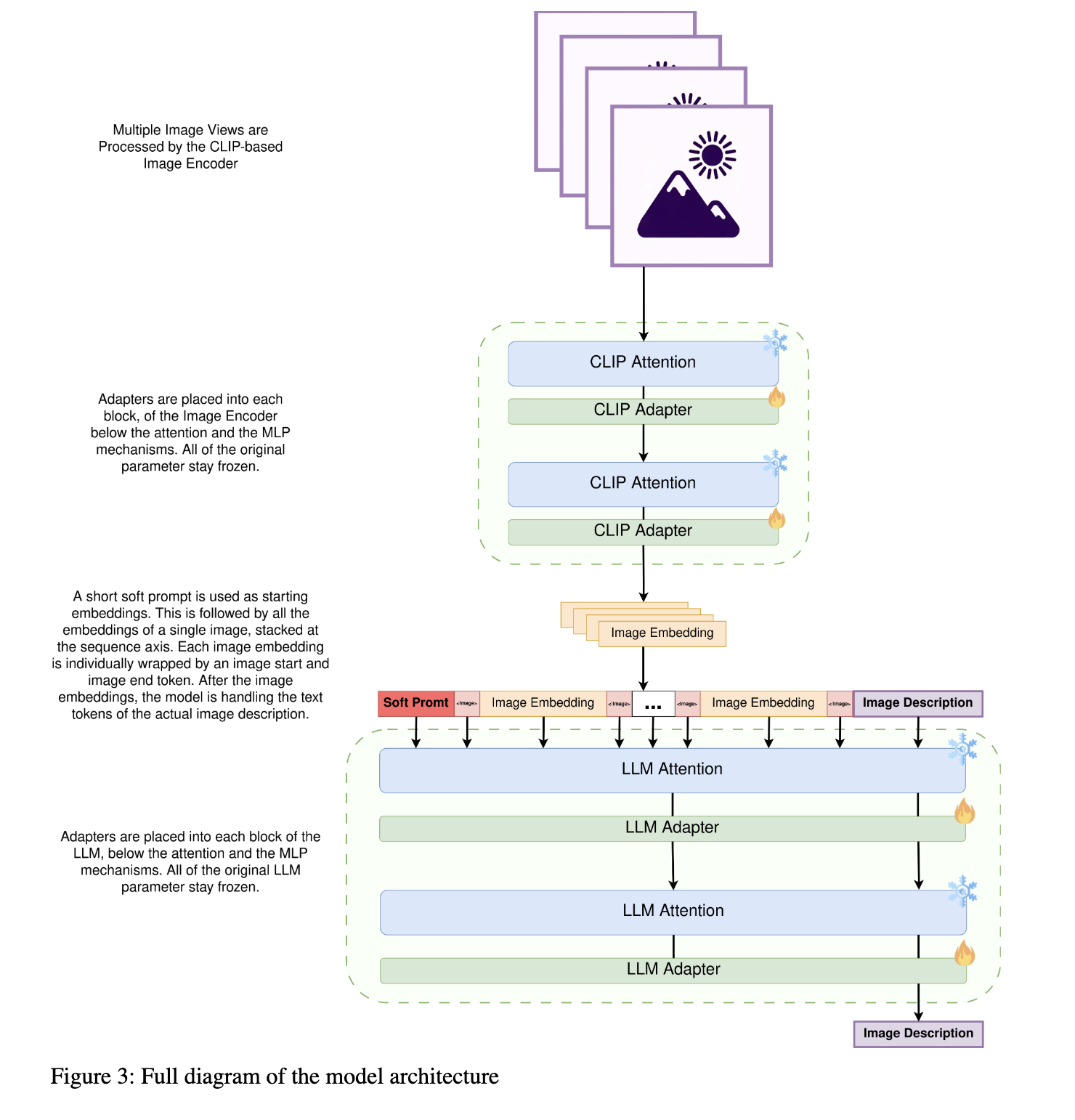

In this technical blog post, I am introducing my new model, AdapterTuneAdvancedCaptioning-QwenVL. It is designed specifically for creating synthetic image descriptions for large-scale datasets. I initially began building the model as a challenge to myself after LAION released their original GPT-V dataset [1]. My goal was to create a model with image captioning capabilities comparable to the original GPT4-V [2], using only personal resources. This means all my experiments and training were conducted on a personal GPU workstation. I achieved this by leveraging a self-QA training loop. This loop broke down the complex task of correcting incorrect image descriptions into many simple Visual QA tasks. I combined this training loop with the strong generalization ability of adapter-based fine-tuning strategies.

This combination allowed me to achieve the same level of detail and accuracy in image descriptions as GPT4-V. There have been several open-source and closed-source multi-modal releases, such as GPT4-V, LLava [3], and Phi-3-vision [4], all designed for human-centric interactions. In contrast, my model is not an instruction-based model. It is purely an image captioning tool designed for the automatic creation of large-scale, high-quality visual image datasets. These datasets can be used for pre-training image generation models like DALLE-3 [5]. This focus on synthetic data generation is also reflected in the writing style of the image descriptions. While other models produce image descriptions that are optimized to sound explicitly nice to humans, my model eliminates all "human-centric fluff". Instead, it outputs image descriptions in a shorthand-like format, similar to a Stable-Diffusion prompt.

Failure Cases of Image Captioning Models

There are two main reasons for an Image captioning model to produce incomplete Image Descriptions. The first one is simply a writing style problem, where the

model mimics the style of pre-training data scraped from the internet, which is composed largely of shorter descriptions which only cover sub-aspects of the image.

Luckily, this is a fairly easy problem to fix, because the model still has learned all of the important underlying Image Text representations. It is just not outputting

them. To fix that, we simply have to fine-tune the model on a small dataset of more complete Image Descriptions, to bring the model to adapt a more detailed image

Description style.

Hallucinations

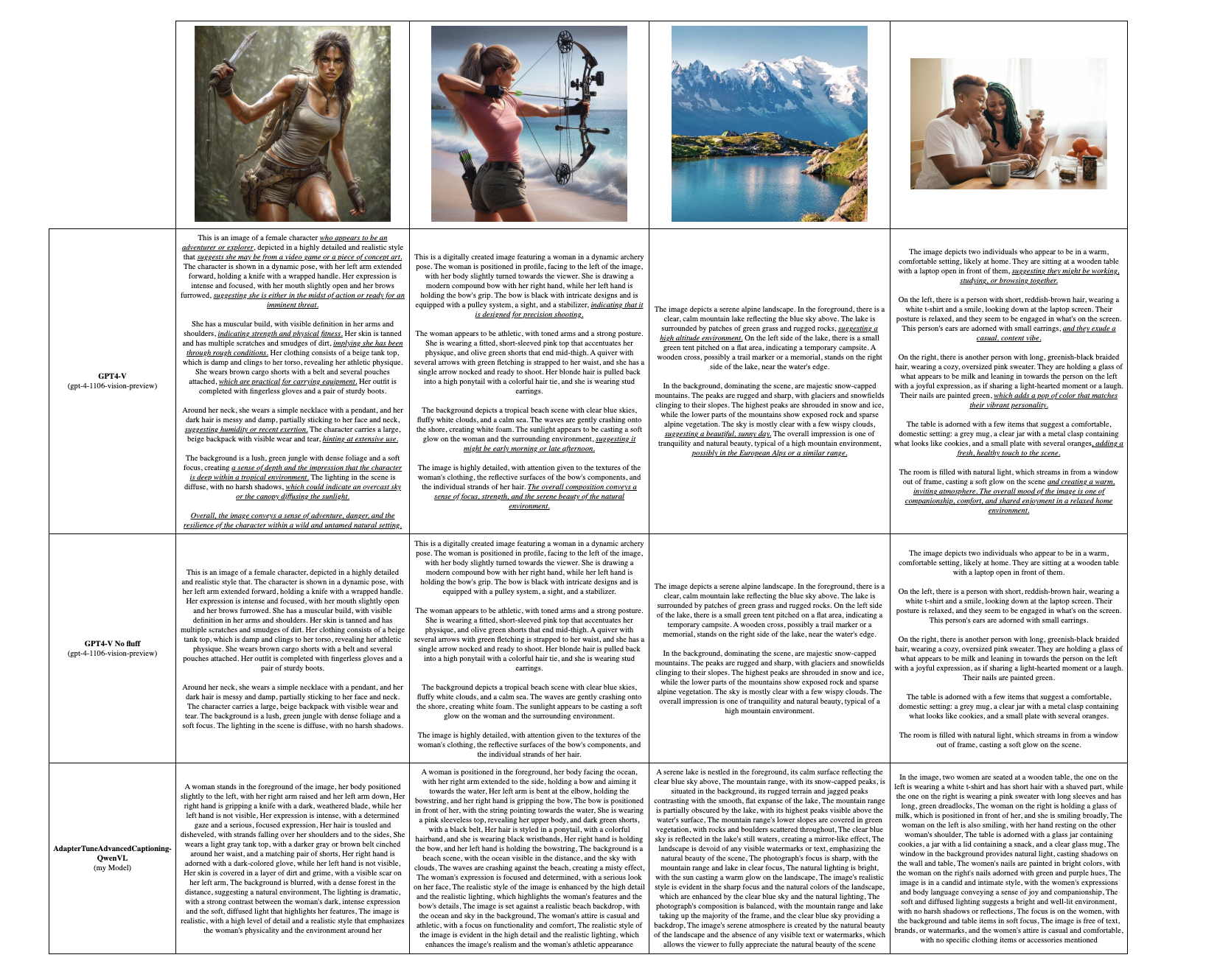

The main reason for hallucinations is a too low a resolution during the pre-training stages. The pre-training for both the Open-CLIP-bigG Image encoder and the qwen-VL pre-training were performed with an image resolution of 224x224 pixels. (qwen-VL had a later second pre-training stage where the image resolution was doubled to 448x448 pixels). Such a low resolution might be enough to capture the general composition of the image, but is inadequate to capture smaller details of the image.

For example, in the original image, the necklace is clearly visible, while in the scaled-down version, it is no longer discernible. A problem arises when the training

image descriptions still contain the information that the woman is wearing a necklace. This, combined with the fact that gradient descent is a local optimization

strategy, meaning it simply tries to find statistical correlations between the input data and the training target. In the best case, the statistical correlations make sense,

and the model learns what a necklace is and how it looks. In the worst case, gradient descent still tries to find some statistical correlations between the input and

target output, but they are completely nonsensical, like determining if a person is wearing a necklace by looking at the person's hairstyle or the lighting in the

background. When the model has learned these nonsensical correlations and is used to describe a new image, it might still predict that the person is wearing a

necklace, despite the person not actually wearing one. Fortunately, these correlations are usually more weakly connected within the model. Because of this, we can

easily remove them by using a negative training feedback strategy, such as RLHF or DPO.

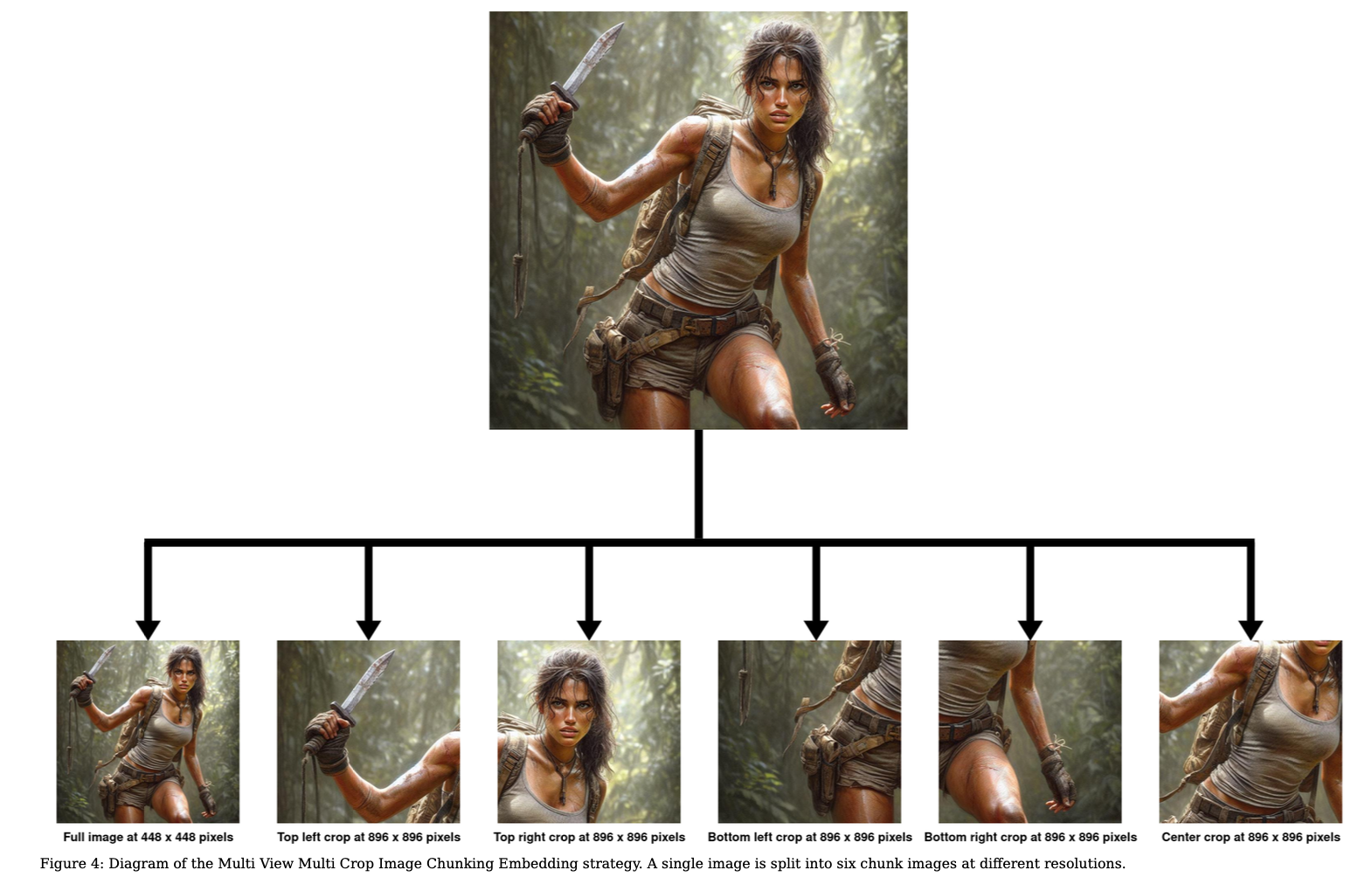

Image Embedding strategy

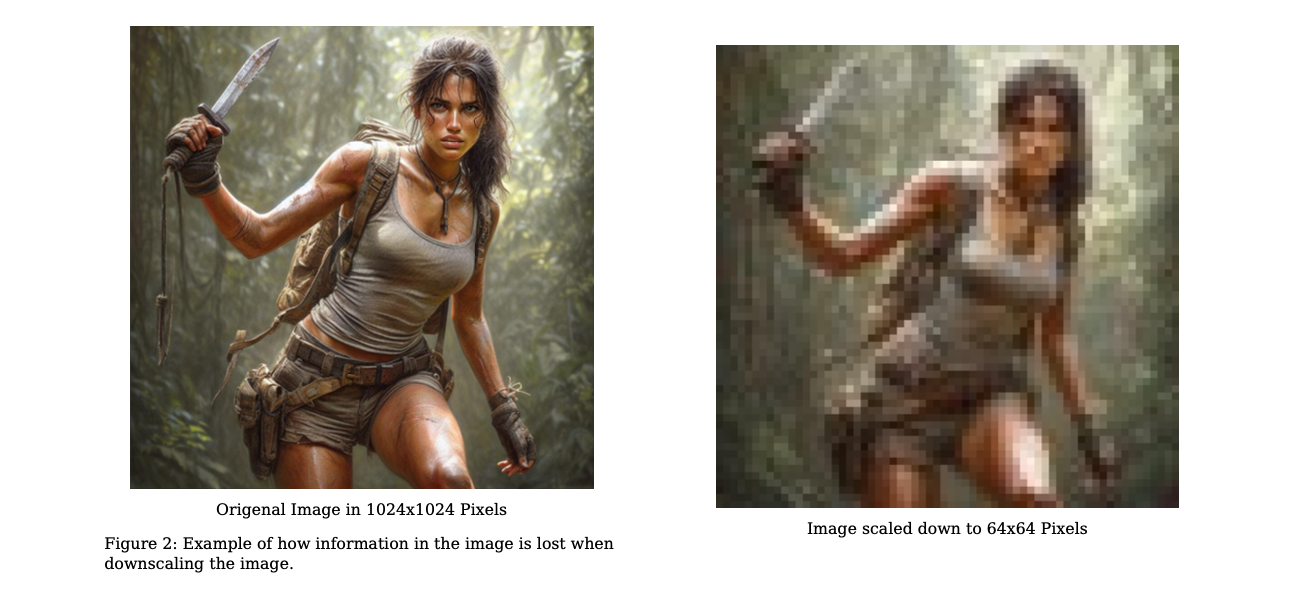

I am introducing a Multi View Multi Crop Image Chunking Embedding Strategy (e.i. MVMCICE Strategy) which chunks an image into multiple crops at multiple

resolutions. Each image is embedded 6 times, at different resolutions.

These changes originate from a desire to increase the overall image resolution, together with the inability to perform an expansive image size adaptation of the Image Encoder. Naively increasing the image resolution would have led to multiple problems. The first one is that Qwen-LV uses a fixed learned Query Attention mechanism to compress the image embeddings into a constant 256 tokens, regardless of the image input resolution. This severely limits the amount of information that the Image Encoder is able to pass to the underlying LLM. Had I naively increased the image resolution, I would have also wanted to increase the number of Embedding Tokens the Image Encoder is allowed to use. Both the change in image input size and re-training the learned Downsampling Queries, would have necessitated an extensive image size adaptation in order to ensure that the long information tail of the model is not severely degraded, which would have required orders of magnitude more compute than initially planned for this project. On the other hand, using the MVMCICE strategy has several upsides. It increases the overall image resolution from 448x448 pixels to 896x896 pixels. This, along with DPO training, helps alleviate the hallucination problem because the model becomes more capable of recognizing smaller objects in the image. The second big advantage is that I get embeddings per image covering a sub-chunk of the image. This is helpful because he embeddings also tend to ignore or fail to embed smaller details. But when the image is also embedded into sub-chunks, then there are fewer objects in the chunk and so even less important details get embedded. This helps to negate one of the primary reasons image captioning models produce incomplete image descriptions.

There are three main decisions/components to the model architecture, the first one is the Image Embedding strategy, the second one is the decision on which parameters to unfreeze, and the third is the selection of the pre-trained base model on which I am building on top of.

What is the Long Tail and Catastrophic Forgetting

But before we can take a look at my decisions, it makes sense to do a quick detour to some underlying training dynamics.

One important concept in deep learning models is the "long tail." If there are enough instances of a given concept in a training set, LLMs can learn robust and parameter-efficient representations of this concept. (In this context, parameter-efficient representations mean that the model can effectively learn common concepts using fewer parameters, while more parameters are required to learn and represent rare concepts.) On the other hand, when there are just a few instances of a given concept, the model needs lots of parameters to learn it. This is called the long tail. One significant reason why the long tail is important is that it helps the model to generalize better. When a model is exposed to a wide variety of rare concepts, it becomes more adept at understanding diverse constructs. This improves the model's ability to robustly handle a broad range of inputs.

Catastrophic forgetting occurs when a model is trained sequentially on multiple tasks or datasets. As the model adapts to new tasks, it tends to "forget" previously learned information, concepts, and patterns. Not all concepts degrade at the same rate during catastrophic forgetting. The first information to go is often the rare concepts contained in the model's long tail. This dramatically degrades the model's ability to generalize. This issue becomes critical when we have a small dataset and a distribution shift between training data and actual use cases. In such scenarios, the model must still generalize well to perform effectively during inference.

Introduction to Finetuning Strategies

Full Model

Full model fine-tuning involves updating all the parameters of a pre-trained model with new data. This process provides the most adaptability for learning new information. However, it comes with the cost of catastrophic forgetting, where the model loses performance on previously learned tasks due to comprehensive parameter updates. I would generally not recommend using full model fine-tuning outside of pre-training dataset scale where the model adapts to a completely new domain, with the expectation that it will lose some of its world knowledge from the previous pre-training. A notable example is the large-scale image pre-training phase that the Qwen-VL model underwent. If the new data significantly differs from the old training objectives, the model may encounter problematic gradients early in the training process, leading to a significant degradation in performance. This issue can arise, for example, during the image encoder adaptation for multi-modal training. To overcome this problem, there are multiple approaches. Qwen-VL employs a multi-stage training setup. Initially, only the image encoder is updated while the base LLM remains frozen. This allows the image encoder to learn an embedding space compatible with the LLM's input space. In the second stage, all the parameters of both the image encoder and the LLM are updated. Meanwhile, MAGMA incorporates adapter parameters, training them alongside the image encoder parameters without unfreezing the original LLM parameters or performing a second pre-training stage.

LoRA

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) introduces trainable low-rank matrices to each layer of a pre-trained model while keeping the original weights frozen. Typically, LoRAs are applied only to the query and value projections within the attention mechanism, significantly reducing the number of trained parameters in comparison to full model fine-tuning. The LoRA weights can be fully fused with the original parameters, adding no extra latency during inference. LoRA is a highly popular fine-tuning strategy due to its low memory footprint and Hugging Face's out-of-the-box support for most models. Another advantage of LoRAs is their small memory footprint, allowing for hundreds or even thousands of different LoRAs to be loaded onto the same GPU and hot-swapped during inference.

However, there are several downsides associated with LoRA fine-tuning. Due to the limited number of trainable parameters, LoRA training is less adaptable than full model training. Additionally, since LoRA modifies some original parameters, it can lead to catastrophic forgetting, although less severe than with full model fine-tuning. It also results in reduced performance when there is a distribution shift between the training data and the inference use case. Despite its popularity in the ML community, I would not recommend using LoRA as the default unless there is a requirement for the lowest possible inference latency or it is explicitly deployed in a setting where many LoRAs are simultaneously kept on a single GPU.

Adapters

Adapters are small MLP blocks added within the Attention and MLP blocks of pre-trained Transformer models. During fine-tuning, only the adapter parameters are updated, while the original model parameters remain untouched. This approach ensures that the fine-tuning strategy does not suffer from catastrophic forgetting. As a result, adapter fine-tuned models tend to outperform full model fine-tuning and LoRAs when a distribution shift occurs between the training data and the actual use case. (A distribution shift can be subtle, such as training on general documents for a QA task and then applying the model to a more specific context like medical QA.) Adapters remain quite parameter-efficient compared to full model fine-tuning, though not as much as LoRAs. Since additional small MLP blocks are added to the base model, they can easily be disabled or swapped with other adapters during inference. Another downside of adapters is that the addition of small MLP blocks increases inference latency. Adapters can handle more data than LoRAs due to their higher parameter count, but not as much as full model fine-tuning. Since none of the original parameters are updated, adapter-based fine-tuning avoids catastrophic weight updates, making it a stable fine-tuning strategy. Overall, I recommend it as the default fine-tuning strategy. Unfortunately, adapters require changes to the model architecture. As such, they are not supported by default by Hugging Face or other popular inference libraries, making them less popular.

SoftPrompt

SoftPrompt tuning involves learning a set of soft prompt vectors, which are prepended to the input sequence of a pre-trained model. SoftPrompt fine-tuning does not update the model's weights; instead, it optimizes the prompt vectors to guide the model in performing a new task. One benefit is that SoftPrompts have a hard time overfitting, even after hundreds of epochs, because they can only steer a language model in a fairly subtle way. This allows SoftPrompts to be trained on datasets with fewer than 10 samples. The downside of SoftPrompts is that the model must already have some ability to perform the given task, or it must be combined with other fine-tuning strategies.

Available Base Model

Over the years, many multimodal models have been made publicly available. Most of these models are based on pre-trained LLMs with an added image encoder and optional additional parameters, while the LLM remains frozen. The original MAGMA model [arXiv:2112.05253] used a CLIP model as its image encoder and added adapters to a frozen, pre-trained LLM. The publicly available MAGMA model was based on the 6B GPT-J model [Kingoflolz] and was trained on 7.6M image-text pairs. Flamingo [arXiv:2204.14198] (not publicly available) and OpenFlamingo [arXiv:2308.01390] build on this idea, using cross-attention layers instead of adapters and directly feeding the CLIP embeddings into the LLM. Flamingo was trained on 2.3B image-text pairs based on a 70B model, while OpenFlamingo was trained on 180M image-text pairs and based on a 7B model.

Another popular multimodal model is BLIP-2 [arXiv:2301.12597]. The largest version of BLIP-2 has 12.1B parameters and is based on a FlanT5xxl model and a ViT-g image encoder. It was trained on 129M image-text pairs. There are also two other noteworthy open-source models trained on large image-text pair datasets: CogVLM [arXiv:2311.03079] and Qwen-VL [arXiv:2308.12966].

CogVLM is based on Vicuna1.5 7B, an instruct fine-tuned and RLHF version of Llama 2 7B, together with an EVA2-CLIP-E 4.4B image encoder. CogVLM duplicates all the MLP and attention parameters and builds with it a fixed routed mixture of experts. The duplicated parameters are enabled on the token positions from the image encoder, while the original parameters are used for text tokens. The two parameter sets connect over the attention mechanism, routing information from the image tokens to the text tokens. During training, all the original parameters remain frozen, while only the duplicated parameters are trained. This prevents catastrophic forgetting of the base model while maintaining high adaptability for image training.

The final model I examined was Qwen-VL. It is based on an early checkpoint of the Qwen 7B model [arXiv:2309.16609] and uses the 2B Laion CLIP model as its image encoder. The image encoder uses a set of 256 learned query embeddings, which downsample the image embedding token dimension to a fixed size of 256 token embeddings. These are then passed to the LLM. This makes the number of embedding tokens independent of the image resolution used. The model was trained in three stages:

- The first stage involved adapting the image encoder embeddings, where the LLM remained frozen and only the image encoder was updated. This was likely done to prevent catastrophic gradients when unfreezing all weights during the second training stage.

- The second stage introduced a large-scale bounding box segmentation task and OCR data-set, along with the standard image captioning task commonly used for training multimodal LLMs.

- The third stage involved adapting the image size from 224x224 to 448x448 pixels.

Overall, the model was trained on 1.4B images.

My Choice

While writing the blog post, I realized I should have chosen the CogVLM model instead of the Qwen-VL model. I was aware of this at the start of the project, but I rejected it because I mistakenly believed it was a full model fine-tuning based on the 13B Stable Vicuna 1.0, an early open-source instruction model derived from LLaMA1. In reality, it is based on Vicuna 7B 1.5, which is built on LLaMA2 7B, with additional instruction and RLHF fine-tuning. This significantly improves performance over the 1.0 versions of the Stable Vicuna models. My second misconception was that I wrongly assumed it to be a full model fine-tuning of a 13B model, when in reality, it was a weight duplication of a 7B model, which keeps all original parameters frozen while adding new trainable parameters. This is highly advantageous as it prevents catastrophic forgetting while providing sufficient model capacity to absorb the 1.5 billion image-text pairs. Another reason I should have chosen the CogVLM model is that Qwen-VL uses learned query embeddings to downsample the number of image tokens to a fixed 256 tokens. Unfortunately, this creates an information bottleneck because the downsampling mechanism relies on the query learning the core concepts which are passed to the LLM. A clear advantage of Qwen-VL over CogVLM is that it has only 9B parameters, including the image encoder and LLM, compared to CogVLM's 17B parameters. This makes Qwen-VL easier to handle and trainable on 24GB GPUs. Another aspect I liked about Qwen-VL is its solid dataset mix, which includes not only image-text pairs but also bounding box annotations and extensive OCR data. This makes Qwen-VL quite proficient at reading text in images. I believe Qwen-VL was a fine base model, but I could have built a substantially better image captioning model with CogVLM.

For my fine-tuning, I primarily used adapters in addition to a small soft prompt. I mainly chose an adapter finetuning strategy because my datasets are relatively small. I had just over 12K samples for the STF and less than that for each preference alignment iteration. Due to the small number of samples, I needed to heavily rely on the base model's generalization capability, making it crucial to keep the base model's long tail intact. Adapters are deployed not only to the LLM but also to the transformer blocks of the ViT-based CLIP image encoder, allowing for its training as well. The Qwen-VL model was trained with a short prompt to distinguish between Chinese and English outputs and to indicate whether object bounding boxes are predicted in line with the image description. Therefore, I am using a short soft prompt initialized from the token embeddings of the English captioning task prompt without bounding boxes. I consider the addition of the soft prompt more of an implementation detail. I am confident that the adapters alone have enough capacity to learn the task as effectively as the combination of adapters and a short soft prompt.

Training Loop

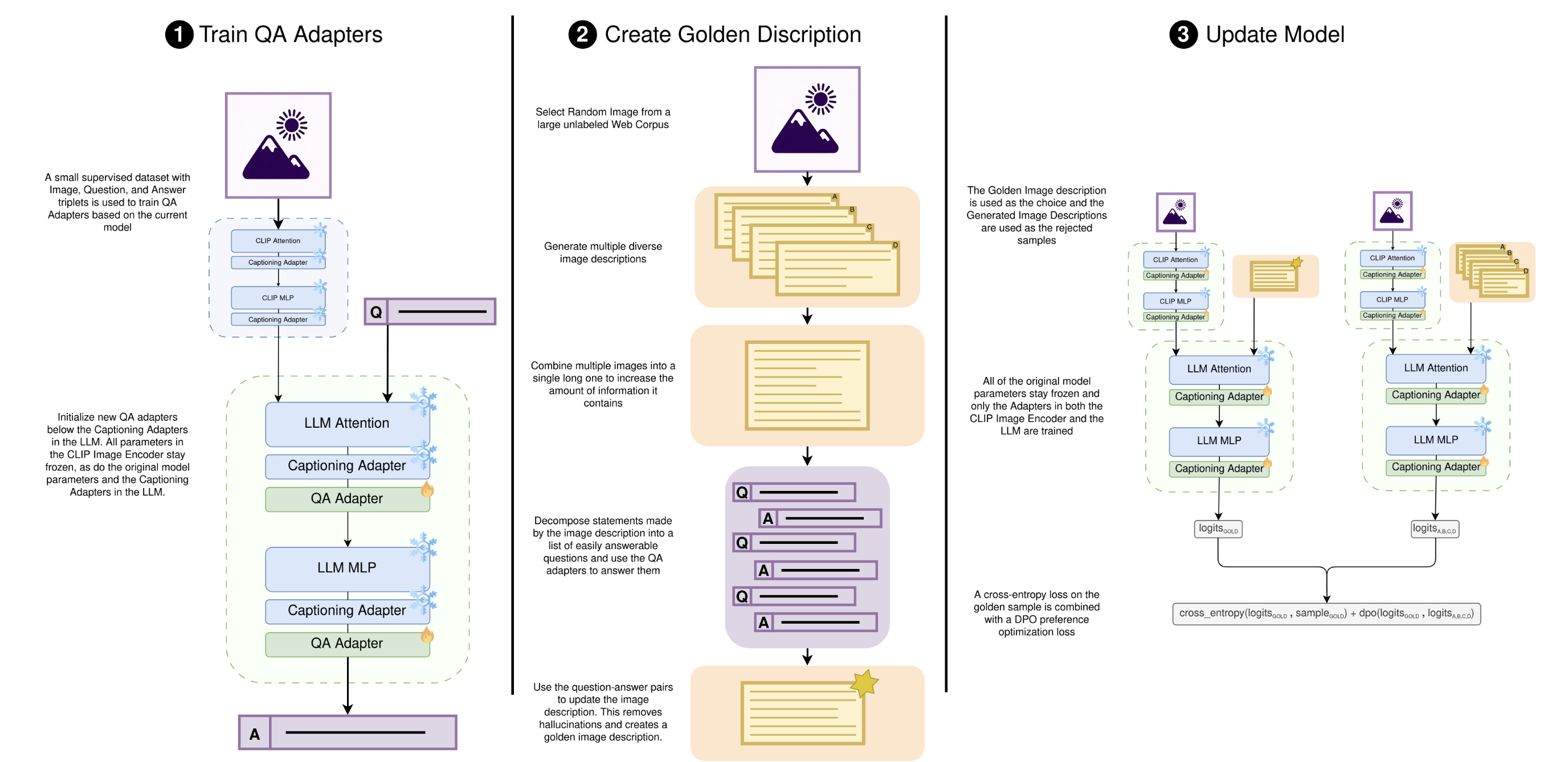

There are three main steps involved in the training loop. The training of QA Adapters, the generation of a golden sample, and a Training step to update the Model.

Training of the QA Adapter

The first step is quite straightforward. I am training a QA model based on the current image Captioning Model in order to ask it questions about the Image. For that, I am initializing a new Adapter below the Captioning Adapter in only the LLM part of the model. No parameter in the CLIP Image Encoder is trained. This has the background that the QA dataset has a narrower distribution than the more general distribution from the Web Corpus used as Image source. Training parameters in the CLIP Image Encoder could lead to a collapse of the image embeddings towards the narrower QA dataset distribution.

The training set of the QA adapter is a small collection (around 2K images) of Image Question and Answer triplets, which are in the style that the question asks if some aspect/object is in the image and the answer then confirms or denies the statement.

Combination of Multiple Generations

In order to increase the information level of the image descriptions, I am generating multiple ones and then combining their content into a single one using a tool LLM. This helps because each description tends to include some different aspects from the image, together with some hallucinations. The resulting combined image description is significantly longer than any of the original image descriptions.

Decomposition into Simple Questions

The combined image description is now a lot longer than image descriptions from the model distribution but also contains some hallucinations. To get rid of the hallucination, I am using again a tool LLM to decompose the statements made in the image description into fine-grained questions about the image, which ask if the statement is true or not. Each image description then results on average in between 30 and 120 questions. Each question is given to the QA model which was trained in step one. The QA model is generally capable of telling if the statement is in the image and true or not, even while using the same underlying model. This has multiple aspects; first of all, it is a lot easier task to answer a direct question than to generate a full image description out of thin air. The second reason why the QA model is generally capable of correcting hallucinations is that most hallucinations are created by sampling with temperature and because of that are coming more from the weaker connections inside the model. The remaining error, which the QA model is not able to filter out, is a statistically acceptable error and will be removed by performing multiple training iterations. The long and de-hallucinated image description is considered a "Golden Sample" and will be used as the positive sample together with the in-model distribution image descriptions as negative samples.

Training

The Qwen-VL model got supervised finetuned with a reformulated version of the LAION GPT4-V-dataset containing around 12K Image Descriptions collected by GPT4-V. A LLM was used to reformulate the human-centric writing style to a more mechanical and shorthand style similar to the prompt style of Stable Diffusion Models. For the supervised finetuning, all adapters in both the image encoder and the LLM were trained together with the embedding soft prompt. For all following preferences alignment iterations, the soft prompt stayed frozen and only the adapters in both the image encoder and LLM continued to be trained.

During the preferences alignment step, I encountered severe training instabilities in the form that the model tended to completely collapse and started to only repeat single nonsensical statements. The exact instability had a strong dependency on the used data shuffling seed, where the same hyperparameters with only different data seed would lead to dramatically different models. I also ablated over different dpo beta values, and over standard DPO, Hinge_DPO, IPO, and KTO. From all of these combinations, only DPO with a batch smaller than 0.1 was able to produce some somewhat usable models 1 out of 4 times. All other Direct preferences alignment methods completely failed to produce a working model. I was able to stabilize the training by combining a DPO loss with a Cross entropy loss on the selected sample. This loss combination dramatically stabilized the training and made it also fairly seed to seed repeatable. My hypothesis on why DPO struggles is that the selected sample is quite far away from the normal model distribution, due to the multisample combination and QA de-hallucination steps.

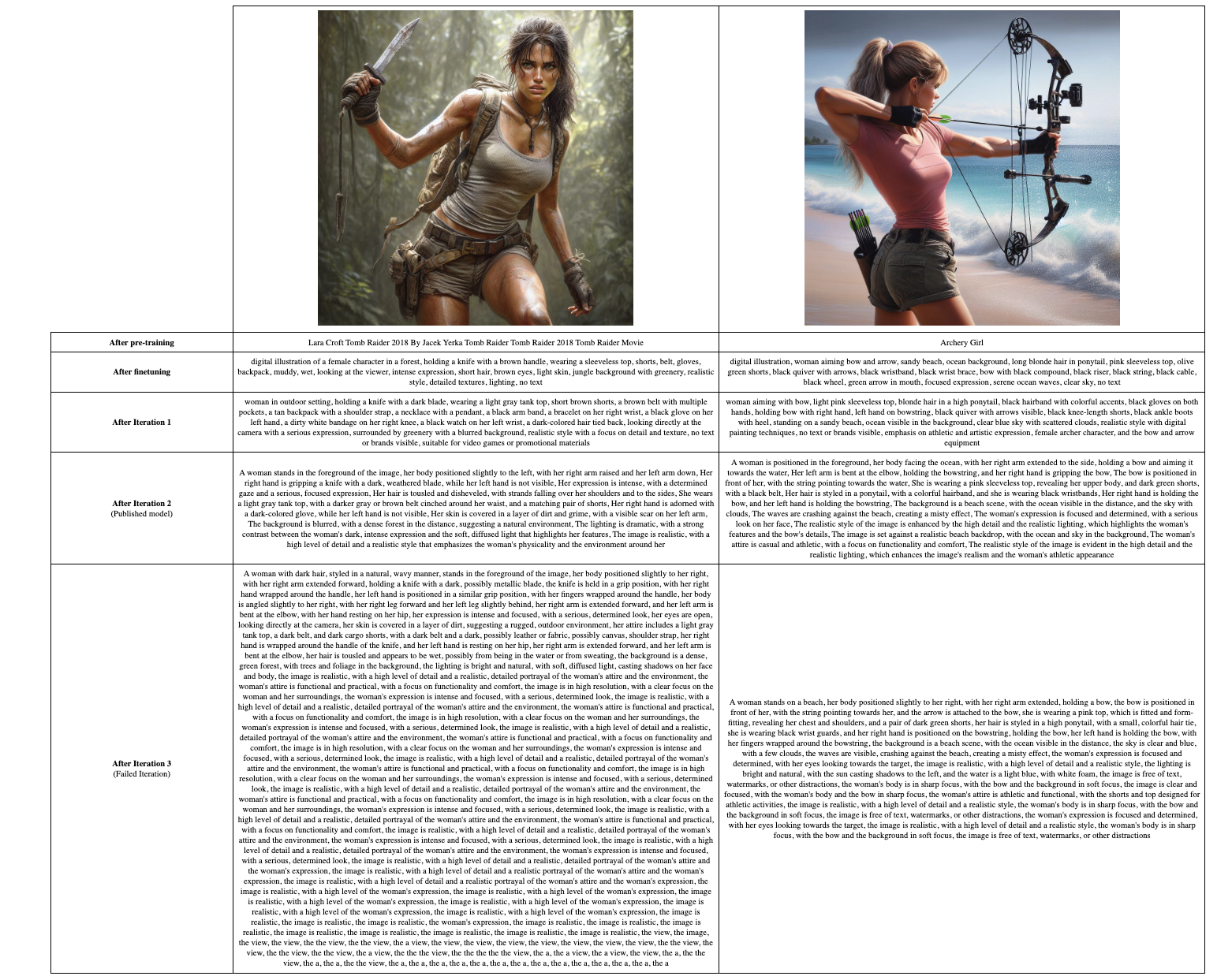

Another common failure case after the supervised finetuning and the first preferences aligned iteration was that the model did not produce an EOS token and instead started to repeat the last made statement indefinitely. This failure case did disappear nearly completely after the second preferences alignment iteration.

I trained for three data generation and preferences alignment training iterations, where the third iteration resulted in a degradation of performance compared to the previous iteration. The published model is the resulting model from the second iteration. I hypothesize that the degradation of the third iteration has mainly the aspect that the image descriptions started to significantly push out of the context size of the pretrained model. Also, it is conceivable that the preferences data generation pipeline, or the used foundation model was pushed over its limit. I did not investigate the degradation of the third preferences aligned iteration or tried to fix it, because the second iteration was already a fairly powerful model, which reached my self-selected goal, of creating an image captioning model as good as GPT4-V.

All experiments, trainings, and preferences data generations were performed on a DIY Hexa 3090 workstation over the course of three months.

Author

XMaster96

References

- OpenAI, "GPT-4V: A Multimodal AI Model," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.openai.com/gpt-4v. [Accessed: 01-Oct-2023].

- Y. Li, H. Zhang, and J. Wang, "LLava: A Large Language and Vision Model," in Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2023, pp. 1234-1245. [Online]. Available: https://www.cvpr2023.org/llava. [Accessed: 01-Oct-2023].

- A. Kumar, S. Patel, and M. Lee, "Phi-3-Vision: Integrating Vision and Language," IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 567-578, May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2023.1234567. [Accessed: 01-Oct-2023].